On this page you can read a number of posts that I published in 2020 and the start of 2021 during the Covid pandemic.

Buy Irish

I am supporting the “Champion Green Campaign”. This is aiming to get people and businesses to pledge to commit to supporting local to help our communities recover. You can find more information by clicking on their logo below, the green butterfly.

With that in mind, below you will find short descriptions of and links to a number of Irish marketplace websites where you can order Irish made gifts, jewelry, crafts, foods, and lots more for delivery to your home.

Note: I hold no interest in these stores, nor have I received any payment – money or otherwise – to display them here. The listings also do not constitute a recommendation of any kind and I am not responsible for any of the services and/or products.

Staycation 2020

2020 will forever be known as the year of COVID-19. The impact on my life has so far been one of inconveniences rather than anything more depressing:

- I have been working from home since early March. I used to travel a lot to meet clients. I was in a plane most weeks, often heading for London and occasionally Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, or Berlin. That has obviously ceased, and I now conduct “meetings” via video conferences.

- I have not been able to visit my widowed mother since January – which I normally do every few months.

- I had to cancel a family trip to Lanzarote, a visit to friends in Iceland, and my planned holiday to Italy.

But let’s look at this another way:

- Thankfully no close relatives or friends have succumbed to the virus.

- I still have my job.

- Thanks to Facetime I am in regular contact with my mother.

- Lanzarote, Iceland, and Italy will still be there next year or the year after.

I don’t want to belittle the stress this crisis brings to people with young families and/or living in small apartments. But I have no sympathy for people who “must” go abroad.

Instead of visiting the Amalfi Coast and Umbria as planned we – my wife and I – are staying put. We are taking a two-week break to recharge our batteries, however. We will be doing a number of day trips, such as:

- a visit to the National Famine Museum

- driving the Mount Leinster Trail

- 14 Henrietta Street

- Marsh’s Library

We also came up with the idea of “theme days”. The first theme day was “Italy”: as we could not go to Italy, we decided to bring Italy do us.

We decorated our house with Italian flags, table cloths, etc. We went shopping in the Specialty Grocery Store “The Best of Italy“. Here we got a lovely “home-made” lasagna for lunch and plenty of fresh ingredients for dinner.

Dinner recipe

- Roast a small quantity of pine nuts. This can be simply done by spreading pine nuts in a single layer in a small frying pan. Don’t use oil, but do stir constantly until the nuts start to go brown. Then move them into a bowl. Don’t leave them in the pan, as they might burn.

- Pasta: cook in lightly salted water. Once done, drain and add a dollop of green pesto and mix thoroughly.

- While cooking the pasta, heat a mixture of vegetables in a frying pan. I chose a red pepper, a large onion, a mixture of mushrooms, and green asparagus. I also added some small cherry tomatoes. Don’t forget the herbs: Italian herbs, Oregano, and fresh Basil (I grow a Basil plant in my kitchen)

- Use pasta bowls to serve; first put in the pasta, cover with the vegetables, and sprinkle with the pine nuts.

- Then there is the cheese. I like to offer both Parmigiano. which I buy ready grated and mature cheddar, which I serve in a grater.

- I chose a white Pinot Grigio to accompany the dinner.

For dessert, we had a home-made Tiramisu. You will be surprised how easy it is to make, but it will take a few hours in the fridge to set, so you will need to do some planning.

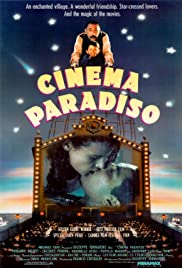

And while enjoying the dinner, we watched a classic Italian movie: Cinema Paradiso, in which a filmmaker recalls his childhood when falling in love with the pictures at the cinema in his home village and forms a deep friendship with the cinema’s projectionist.

National Famine Museum | Strokestown Park

In the nineteenth century, most land in Ireland was owned by a small elite of – mostly – Protestant landlords. They would rent out their land to tenants or would have large estates cultivating land directly (the “Demesne”). Often it was a combination of the two. Some landlords would live on their estate, but others would not, leaving the management to middlemen. It was also not uncommon for landlords to own multiple estates. The Irish estates were an investment, run to provide a return for their owners. However, many estates had ceased to be profitable even before the famine of 1845 – 1849. The famine threatened their viability even further, as many tenants could no longer afford to pay rent. The famine afforded however also an economic opportunity, of which more later.

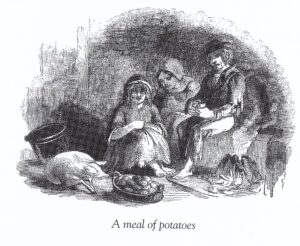

Poverty

But let’s step back in time a bit further. Even before the famine, poverty was widespread in Ireland. It had 8 million inhabitants (today, 170 years later, the number is 6 million) and many Irish had to compete for work as landless labourers. Others would be tenants, but the growing population meant that many of their holdings had been subdivided into smaller and smaller plots of lands with each generation. For a lot of Irish people, the potato was their only source of food, as it was nutritious and cheap. Some would be able to afford bread and only a few meat. The “Board of Works” had been established in 1831 to deal with this poverty, by offering work to the unemployed on public works.

Famine

The famine was not caused because there was no food. As a matter of fact, Ireland still exported grain throughout the famine years of 1845-1849. The cause was a potato disease, called “blight”, making them inedible. The potato shortage also pushed the prices of other foods up. As a consequence, most simply could not afford any food anymore. Unfortunately, the “Board of Works” was completely overwhelmed, and by 1846 its failure was widely accepted.

Relief efforts

An attempt at relief for the Irish poor was the purchase and sale of cheap grain. The budget was £100,000, or about £12 million in today’s money. To maximise the amount of grain, so-called “pigs-grain” (it was deemed only suitable as animal feed in India, where it came from) was bought. It required three times the amount of labour to turn it into usable flour, using heavy-duty utensils, as shown in the pictures below.

But Trevelyan, who was in charge of emergency food supplies in Ireland during the famine, advocated a policy of effectively withholding relief and allowing market forces to take their course. As the importing and selling of cheap grain by the government was deemed to be distorting the proper working of the free market, it was discontinued in 1847.

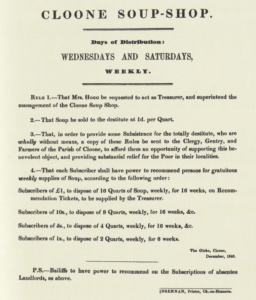

Private relief efforts did not fare much better. Best known of these efforts are the “Soup Kitchens”, where cheap soup was sold. However:

“Nicholas Soyer was a French Chef at the Reform Club during the famine. The soup he devised for the victims of the famine was pronounced excellent by members of high society who visited his Model Soup Kitchen in Dublin. However, it was widely attacked for its lack of real nutritional value. One meal of Soyer’s soup only provided one-tenth of the necessary daily intake of calories.”

“Nicholas Soyer was a French Chef at the Reform Club during the famine. The soup he devised for the victims of the famine was pronounced excellent by members of high society who visited his Model Soup Kitchen in Dublin. However, it was widely attacked for its lack of real nutritional value. One meal of Soyer’s soup only provided one-tenth of the necessary daily intake of calories.”

National Famine Museum

The Quakers – who were heavily involved the running of soup kitchens – concluded in the end that without fundamental reform, their attempts were futile.

Which left the local Unions running Workhouses. They were also completely swamped by the famine. The authorities responded by increasing their number and expanding the existing ones. The problem was that they were financed by contributions made by landlords, based on the number of poor tenants they had.

This led to the next phase in the development of the famine. Landlords now had an incentive to get rid of their poor tenants, as well as an excuse (as the Unions were supposed to look after the evicted tenants).

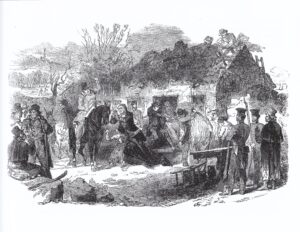

Evictions

“.. the change from an idle barbarous isolated potato cultivation, to a corn cultivation, which enforces industry, binds together employer and employed in mutually beneficial relations, and, requiring capital and skill for its successful prosecution, suppose the existence of a class of yeomanry who have an interest in preserving the good order of society, is proceeding as fast as can reasonably be expected.”

Charles Trevelyan, Secretary of the Treasury, The Times, 12 October 1847

As per the statement above, not only would the eviction of tenants reduce the taxes estates had to pay, but it also offered estates a much more profitably future: many estates were inefficient and badly managed before the famine, with many small sub-holdings. Switching to the growing of grain and the rearing of cattle on large farms was a much better economic proposition. And this required getting rid of the small plots and a lot fewer tenants.

Strokestown

Strokestown was an estate of about 11,000 acres and had its own village attached to it. It was owned by the Mahon family. Major Denis Mahon had inherited it in 1845, just when the famine started. The estate was not in a good position: a previous member of the family had run up debts by significantly enlarging the mansion. He was followed by his bother who was mad; and after that, there were 10 years of legal cases to determine who would inherit. For all of this time, it had been badly managed.

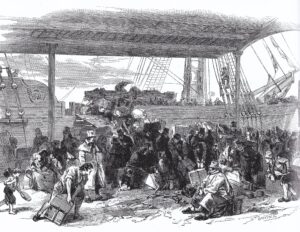

To rescue his estate, Major Denis needed to reform, which meant getting rid of his tenants. Like other estates, Strokestown did offer incentives to tenants to emigrate, including forgiveness of debt and payment of passage. About a thousand Strokestown residents would take up the offer. But the ships the estate chartered did justice to the name “coffin ships”, with over a third of their human cargo not surviving the trip.

To rescue his estate, Major Denis needed to reform, which meant getting rid of his tenants. Like other estates, Strokestown did offer incentives to tenants to emigrate, including forgiveness of debt and payment of passage. About a thousand Strokestown residents would take up the offer. But the ships the estate chartered did justice to the name “coffin ships”, with over a third of their human cargo not surviving the trip.

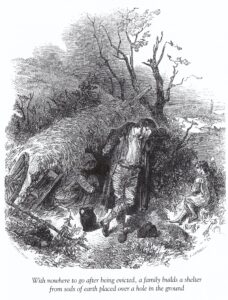

And it was nowhere enough for the heavily indebted estate: by late 1847 Strokesdown had become a byword for mass evictions. Strictly speaking, the estate could only evict tenants from their land, not their house. But the landlord also controlled who would be registered for relief with the Unions. And the condition invariable was that the tenants would leave their house as well. Which would subsequently be demolished to prevent them from being re-occupied.

This obviously created tensions. Priests in the Catholic Church were often accused of inciting violence and disobedience, and the local priest in Strokestown was accused of having a role in what was to follow. Most priests would preach obedience to law though, so it is more than likely that a “secret society” of disgruntled locals was responsible for the shooting dead of the landlord of Strokestown: on 2 November 1847 the patriarch of the family, Major Dennis Mahon was assassinated. It is this event that made him famous, as he was the first landlord to be killed. Other assassinations would follow and soon almost every landlord would fear for their lives. Quite a few decided to leave Ireland.

Modern Times

The estate did survive, however. The last member of the Mahon family to live on the estate, Mrs. Olive Hales Pakenham Mahon, moved to a nursing home in England only in 1981, at the age of eighty-seven.

She had already sold the estate in 1979 to a group of local businessmen. They started a much-needed restoration; it was in a very bad state of repair as Olive Mahon had run out of money. A consequence of the latter is that a lot of the features and fabrics are original, as there never had been money for replacements. This did not include the paintings, as they had been sold off a long time ago to generate some income. But it does include a beautiful kitchen that is 200 years old. The gallery below gives you an impression.

The new owners did find a large collection of estate and family papers which formed the basis of the development of the National Famine Museum on the premises of the house. You can visit the museum, as well as the house and its walled garden. For more information, click here.

Gallery

Click the picture to read the accompanying note.

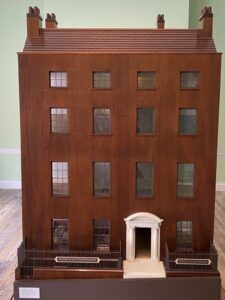

14 Henrietta Street

Luke Gardiner was a property developer in Dublin in the 18th Century. He developed large parts of Dublin City north of the river Liffey and became very wealthy in the process.

Probably his most upmarket development was Henrietta Street, laid out during the 1720s. This is a very short street, now known for The Honorable Society of King’s Inns building at the top. This is however of a later date, its foundation stone was laid “only” in 1800.

Henrietta Street was aimed at the very top of Irish society: nobility, senior clergy, top judges, and Luke Gardiner himself. Many of them would have seats in the Irish Parliament, either elected or through hereditary rights. For several of them this was their city house, as they also owned substantial mansions down the country.

The houses on Henrietta are very large Georgian buildings. Number 14, of which more below, measures 9,000 square feet over 4 floors and a basement. The basement would contain the kitchens and storage space, it is where the staff would toil. The ground floor would be the main living space for the family. The Piano Mobile or first floor would have several reception spaces for entertaining guests. The top two floors were bedrooms and nurseries.

The houses on Henrietta are very large Georgian buildings. Number 14, of which more below, measures 9,000 square feet over 4 floors and a basement. The basement would contain the kitchens and storage space, it is where the staff would toil. The ground floor would be the main living space for the family. The Piano Mobile or first floor would have several reception spaces for entertaining guests. The top two floors were bedrooms and nurseries.

The first family to live in the house was the family of Robert Molesworth, who was a powerful politician who was created a Viscount in 1715. He was followed by several other rich and powerful occupants, such as The Right Honorable John Bowes, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Sir Lucius O’Brien, John Hotham Bishop of Clogher, and Charles 12th Viscount Dillon.

That all changed in 1801. In that year, England’s leaders decided to centralise power. They had become worried because of the French Revolution, which has led to unrest in Ireland as well. By convincing and bribing members of Parliament, they succeeded in getting the parliament to vote for its own abolition. Powers were transferred to the parliament in London.

Soon the rich and powerful left Henrietta Street. They were at first replaced by legal people, lawyers, solicitors, barristers, etc. This included Number 14. In 1850, it became a temporary courthouse at the end of the Great Famine, dealing with the affairs of the many bankrupt country estates: the Encumbered Estates’ Court.

When this was no longer needed it was for a while used by the English army as a barracks until 1876. Thomas Vance bought the property and turned it into a tenement, by stripping out all valuable decoration – such as marble fireplaces – and subdividing many of the rooms. Since the famine, many Irish had descended on Dublin and there was a desperate shortage of housing. Just after the turn of the nineteenth century, there were over 100 people living in 14 Henrietta Street. It was an “open door” building, which means the front door was never locked. During the night vagrants would come in and sleep in the corridors.

It had no running water; and only two toilets. It was heated by open fires, which were also used for cooking. Lighting was by means of candles and oil lamps. It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that gas and electricity was introduced.

Bugs and vermin would also be a continuous problem. It was said that residents arriving in the dark, would kick the stairs to scare away the rats. Floorboards were in a bad state; in many places you could see through them to the floor above or below. In many rooms there were holes in the floor.

Bugs and vermin would also be a continuous problem. It was said that residents arriving in the dark, would kick the stairs to scare away the rats. Floorboards were in a bad state; in many places you could see through them to the floor above or below. In many rooms there were holes in the floor.

Still, 14 Henriette Street was an “A” class tenement. “B” class were worse and “C” class were often sheds or stables.

The famous strike known as the “Lock Out” early in the century was a failure. But it did bring the appalling living conditions of many Dubliners out in the open. Action was delayed because of World War I, the War of Independence, the Civil War, and the creation of the Irish State. Plans were finally made in the 1920s and construction of suburbs started in the thirties. These provided much improved and healthier living conditions, although not the same sense of community. When several tenements collapsed in the sixties, it gave a renewed impetus to the building of modern housing. Apart from more suburban developments, this was also the time that Ballymun was developed. As per above, it was not until the seventies though that the last tenements were closed.

Number 14 was allowed to decay. As part of the Henrietta Street Conservation Plan, the local council bought the house after 2000. It started a long renovation process and it opened to the public in 2018, telling the story we have related above. For more information click here.

Tenement living around 1900

An impression of a tenement room around 1900. No blankets. Instead, coats were used to keep warm during the night.

Tenement living in the fifties

Living room – with beds for the children, master bedroom, and kitchen.

Hillwalk and Garden in Dalkey

Dalkey is a former village and now a suburb of Dublin. It is located in the South-East of the city. It traces its origins to Viking times and was a busy port town in the Middle Ages.

I have visited the attractive town itself many times. This time I went for a walk in Killiney Hill Park and a visit to Mornington Garden.

Killiney Hill Park

This park takes in both Killiney Hill and Dalkey Hill. It was opened to the public as far back as 1887, by Prince Albert, and was then called Victoria Hill, in memory of her Jubilee.

The park offers spectacular views over the surrounding areas: Dublin to the northwest, the Irish Sea to the east and southeast, and Bray Head and the Wicklow Mountains to the south. Here are some pictures I took:

Mornington Garden

Afterwards, I visited Mornington garden, which is a private garden just outside the entrance to the park. It is by appointment only and costs €6 per person, minimum group of 4. Our very knowledgeable host was Annmarie Bowring who gave a very enthusiastic tour of her beautiful garden. And gave me lots of tips and ideas for my own (she also runs a garden school). These are just a very small sample of the many flowers in her garden. If you are into gardening, I would recommend a visit! For more information, click here.

Happy Christmas 2020

2020 has been an awful year. Most of us would like to forget it and move on. Unfortunately, we will all need more patience. It will take time before the vaccines will become readily available and it will need 60-80% of people inoculated before it is truly effective. This means we will spend most of 2021 socially distancing, wearing masks, etc. That idea might be disturbing for some. But think of this.

My heart goes out to those that have lost dear ones. And it is exactly because of that we need to keep strong. Otherwise, we will cause just more grief.

This means that Christmas 2020 has to be different. No big family gatherings in Ireland, no visits to my family in The Netherlands.

But my family is still healthy. I am still in a job. I will still take the Christmas week off for some relaxation and enjoy the company of my wife, and for Christmas, my mother in law, with whom we are in a “bubble”. I will still enjoy this Christmas. Just the way I enjoyed my holidays, even though it wasn’t in Italy as planned, but just a few day-trips in Ireland.

So, rather than complain about the things we cannot do, let’s appreciate the things we can. And with that, I wish you:

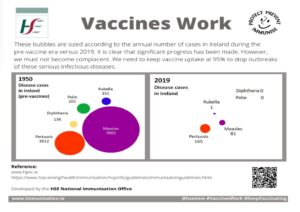

Vaccines Work!

I would like to start to say that I am not a specialist in this area. Or any medical area for that matter. The below is based on what I have read in, and been told by what I would consider reliable – scientific, medical – sources.

I was very happy this last week to get my first dose vaccination against Covid-19. I got the Pfizer Biontech one in Dublin’s CityWest based vaccination centre. It was done very efficiently, in and out in just over an hour. Thankfully no side effects, as I understand is the case for the vast, vast majority of people.

I won’t be able to change my behaviour yet though. It will take approximately 2 weeks for this first dose to be effective. After that, I can still get the virus – and transmit it – but the likelihood of getting seriously ill or worse should be very small. It is only after the second dose has taken effect (1-2 weeks after getting the dose, which is planned in about 4 weeks from now) that the likelihood of getting the virus at all becomes much less.

Which would bring me to somewhere in July. But after having been in lockdown or semi-lockdown for 14 months, a few more months does not sound too bad.

I am, however, very much looking forward to a holiday I booked for later in the year. I booked it a few months ago in the hope that we would be where we are expected to be now – personally AND as a country: fully vaccinated myself and 70-80% first dose vaccination in the country. We expect to reach the latter in July/August.

I am still careful. I have booked a holiday in Ireland, thus avoiding the crowds of airports. And I intend to do plenty of outdoor activities. So here is hoping for good summer weather!

It could still go wrong. We might see another spike, another variant. But I am hopeful for the future. And there is something that we all can do to prevent another setback: keep wearing masks, keep social distancing, etc. And when you are offered the vaccine, take it! Because vaccines work, as you can see from the below graph taken from the hse.ie website: